Do you eat when you’re bored, not hungry? Do you finish a meal and still feel like something is missing? You might be eating for dopamine, not fuel. And you’re not alone.

If you’ve spent years feeling like you’re fighting your own brain around food, I want you to know something: it might not be about willpower. It might be about wiring.

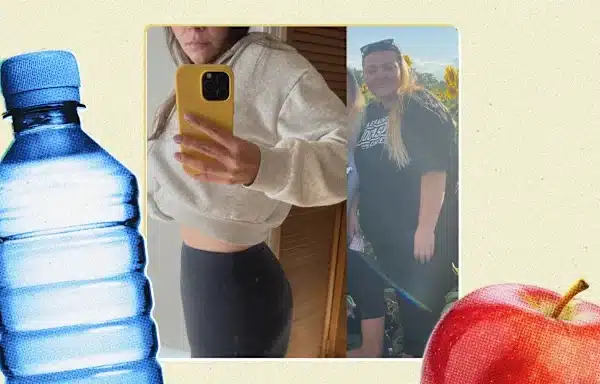

After performing over 7,800 bariatric surgeries and working with patients from across the United States and Mexico, I’ve identified a pattern that most surgeons overlook. Women in their 30s, 40s, and 50s who have tried everything (diets, programs, medications) yet continue struggling with eating patterns that feel out of control. Many of them share similar stories: forgetting to eat for hours, then suddenly ravenous and unable to stop. Eating past fullness but still not feeling satisfied. Using food to focus, to decompress, to feel something.

And increasingly, many of these same women are receiving a diagnosis that finally makes everything click: ADHD.

Research shows that approximately 30% of adults with binge eating disorder also have a history of ADHD. In bariatric surgery candidates specifically, studies find ADHD prevalence ranging from 20-27%, far higher than the general population. And here’s what makes this particularly relevant: most women with ADHD aren’t diagnosed until their late 30s or early 40s, often after years of being told their struggles are about discipline, motivation, or emotional eating.

This is a topic I’ve studied extensively and discuss with my patients regularly. I want to explain why ADHD and weight are so deeply connected, what “dopamine hunger” actually means, and what this means for your success with bariatric surgery.

The ADHD-Obesity Connection: It’s About Your Brain, Not Your Character

ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) is fundamentally a disorder of the brain’s dopamine and norepinephrine systems. These neurotransmitters regulate our ability to focus, control impulses, regulate emotions, and, crucially, feel satisfied.

People with ADHD typically have lower baseline levels of dopamine, the brain’s primary “reward” chemical. This creates a brain that is constantly searching for stimulation to function normally. It’s not about wanting more pleasure. It’s about needing more stimulation just to feel baseline “okay.”

And here’s where food enters the picture.

Food, particularly sugary, salty, or fatty food, produces a rapid spike in dopamine. For someone with a dopamine-deficient brain, eating provides something neurologically significant: relief. Focus. A sense of completion. The problem is that this relief is temporary, and the brain quickly returns to its understimulated state, creating a cycle that can look and feel exactly like addiction.

Why This Matters for Weight

Research has identified several pathways connecting ADHD to obesity:

1. Impulsivity and reward-seeking: ADHD brains are wired to seek immediate rewards. The delayed gratification required for long-term weight management is genuinely harder for these brains to sustain.

2. Executive function deficits: Planning meals, grocery shopping, meal prep, following through on diet plans—all require executive functions that ADHD directly impairs.

3. Emotional dysregulation: Up to 70% of adults with ADHD experience significant emotional dysregulation. When emotions feel unmanageable, food becomes a regulator.

4. Interoception challenges: People with ADHD often struggle to recognize and interpret internal body signals—including hunger and fullness cues.

5. Medication effects: Some ADHD medications suppress appetite during the day, leading to under-eating followed by overeating at night when medication wears off.

The result? One large study found that children with ADHD symptoms were significantly more likely to be obese by age 16, and that ADHD symptoms predicted later obesity—not the other way around.

Signs You’re “Stimulation Eating,” Not Hungry

One concept that has resonated deeply with many of my patients is distinguishing between true hunger and stimulation-seeking. Understanding the difference can be transformative.

You Might Be Eating for Stimulation If:

- You eat when you’re bored, even if you just ate

- You feel driven to eat when you’re procrastinating or avoiding a task

- You need to eat while doing something else (scrolling, watching TV, working)

- You finish a meal and still feel like something is “missing”

- You seek out intensely flavored foods (very sweet, salty, crunchy, spicy) even when milder options are available

- You eat rapidly, barely tasting food

- You feel a “need” to eat that feels urgent and non-negotiable

- Food is the first thing you think of when you need a break

- You eat past physical fullness but don’t feel satisfied

- You have difficulty stopping once you start eating certain foods

True Hunger Usually Feels Different:

- Comes on gradually

- Isn’t tied to a specific food

- Can wait

- Stops when you’re full

- Doesn’t feel urgent or anxious

- Isn’t connected to emotions or situations

If the first list resonates more than the second, your eating patterns may be more about dopamine than about hunger—and that’s crucial information for your treatment plan.

The Interoception Problem: When Your Body Doesn’t Send Clear Signals

There’s another piece to this puzzle that doesn’t get discussed enough: interoception.

Interoception is your brain’s ability to sense and interpret what’s happening inside your body: hunger, fullness, thirst, fatigue, even emotional states. It’s what allows you to know you’re hungry before you’re starving, or to recognize when you’ve had enough to eat.

Research shows that people with ADHD often have significantly impaired interoception. In my years of working with bariatric patients, I’ve heard this described in remarkably consistent ways:

“I don’t feel hungry gradually—I’m either fine or suddenly starving.”

“I can forget to eat all day when I’m focused on something, then eat everything in sight at night.”

“I never know when I’m full. I just stop when the food is gone.”

“I confuse being tired with being hungry. Or anxious with hungry. Or bored with hungry.”

When your body doesn’t send reliable signals about when to eat or when to stop, eating becomes governed by external cues (seeing food, smelling food, the clock, other people eating) rather than internal ones. This makes maintaining a healthy weight extraordinarily difficult—and it’s not a character flaw. It’s neurology.

The Dopamine Menu Concept: A Tool for Understanding Your Brain

You may have encountered the concept of a “dopamine menu”, a framework popularized by ADHD educator Jessica McCabe. The idea is simple but powerful: since ADHD brains are constantly seeking dopamine, we can proactively create lists of activities that provide stimulation at different intensities, rather than defaulting to easy (but often unhelpful) dopamine sources like food.

I teach this concept to my patients because it works. Think of it like an actual restaurant menu:

Appetizers (quick, low-effort boosts):

- Listening to an upbeat song

- A short walk

- Stretching

- A cold drink

- Playing with a fidget toy

Main Courses (more sustained, fulfilling activities):

- Exercise

- A creative project

- Social connection

- Learning something new

- Completing a task

Desserts (easy but easy to overdo):

- Social media scrolling

- Shopping

- Video games

- Snacking

- Binge-watching shows

Specials (occasional, high-investment activities):

- Travel

- Concerts or events

- Major purchases

- New experiences

The insight here is that all of these activities are forms of dopamine-seeking—and that’s okay. The question is whether you have options other than food when your brain needs stimulation.

For my patients, especially post-surgery, building a robust dopamine menu is not optional—it’s essential for long-term success.

ADHD and Bariatric Surgery: What the Research Shows

This brings us to the question many patients ask: Can I still have successful bariatric surgery if I have ADHD?

The answer is yes, but with important nuances. I’ve operated on hundreds of patients with ADHD and have developed specific protocols based on this experience.

The Good News

Weight loss outcomes are similar. Multiple studies show that patients with ADHD achieve comparable weight loss to non-ADHD patients after bariatric surgery. A 2024 retrospective study specifically found that bariatric surgery was “highly effective and underutilized” in patients with ADHD, with the ADHD surgery group showing the largest BMI decrease over 5 years.

A large Swedish study following over 4,000 patients (1,431 with ADHD) found no significant difference in weight loss or remission of obesity-related diseases at 2 years post-surgery.

Some ADHD symptoms may actually improve. One study found that ADHD-related symptoms like inattention/memory problems and negative self-concept were lower in post-surgery patients compared to pre-surgery candidates. Researchers hypothesize that the cognitive benefits of weight loss and improved health may partially help executive function.

The Challenges

Follow-up attendance is lower. Multiple studies consistently show that patients with ADHD are less likely to attend post-operative follow-up appointments. This is concerning because follow-up is directly correlated with better long-term outcomes. In my practice, I address this proactively with specific support systems.

Higher risk for certain complications. The Swedish registry study found that ADHD patients had:

- Higher early postoperative complication rates

- Increased risk of substance abuse post-surgery

- Increased risk of self-harm behaviors

- Lower overall quality of life scores

Medication adjustments may be needed. Bariatric surgery changes how your body absorbs medications. A 2025 pharmacokinetics study found that the absorption of ADHD medications like lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) actually increased after surgery, meaning dosages may need adjustment.

The Bottom Line

ADHD is not a contraindication for bariatric surgery, but it does mean we need to plan differently. Patients with ADHD benefit most from:

- Comprehensive pre-operative psychological evaluation

- ADHD treatment optimization before surgery

- Extra support systems for follow-up attendance

- Explicit planning for dopamine-seeking behaviors post-surgery

- Monitoring for transfer addiction risks

Transfer Addiction: The Critical Risk for Dopamine-Seeking Brains

This is something I discuss extensively with every patient who has ADHD or a history of using food for emotional regulation: transfer addiction (sometimes called cross-addiction or addiction transfer).

Here’s the reality that every bariatric patient needs to understand: surgery physically restricts how much you can eat. But it doesn’t change your brain’s dopamine system. If you were using food to regulate your emotions, manage stress, and seek stimulation, that need doesn’t disappear after surgery. The food just stops working as well.

Research shows that up to 30% of bariatric surgery patients develop some form of transfer addiction. The most common new behaviors include:

- Alcohol use (this is the most documented and concerning)

- Shopping or spending

- Gambling

- Internet/social media overuse

- Exercise (which can become compulsive)

- Sexual behaviors

- Even drug use in some cases

The risk is particularly high for people with:

- History of binge eating or food addiction

- History of any substance use disorder

- ADHD or other conditions affecting impulse control

- Pre-operative emotional eating patterns

One large study (the LABS-2 cohort) found that 20% of patients who had Roux-en-Y gastric bypass developed alcohol use disorder within 5 years, compared to 11% of those who had gastric banding.

Why Alcohol Is Especially Dangerous After Surgery

This is something I emphasize with every single patient. After bariatric surgery (especially gastric bypass and gastric sleeve), your body metabolizes alcohol completely differently:

- Alcohol is absorbed faster into your bloodstream

- Blood alcohol levels rise higher

- Effects are felt more intensely

- It takes longer for your body to clear the alcohol

Many patients report feeling intoxicated from a single drink after surgery. This heightened response can make alcohol much more reinforcing (and addictive) than it was before.

My recommendation: Complete abstinence from alcohol for at least the first year after surgery, and extreme caution thereafter. For patients with ADHD or a history of emotional eating, I often recommend extended or permanent abstinence.

Vyvanse: The FDA-Approved Medication for Both ADHD and Binge Eating

There’s a remarkable overlap in how we treat ADHD and binge eating disorder, because they share underlying neurobiology.

In 2015, lisdexamfetamine (brand name Vyvanse) became the first and only FDA-approved medication specifically for binge eating disorder in adults. It was already approved for ADHD in 2007.

Vyvanse works by increasing dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain. For people with binge eating disorder, this means:

- The brain gets more dopamine from its normal sources

- The desperate drive to seek dopamine through food decreases

- Impulse control improves

- Obsessive thoughts about food reduce

Clinical trials showed that patients taking Vyvanse experienced significantly fewer binge days per week compared to placebo. In one study, 50% of patients on the highest dose (70mg) achieved a binge-free month, compared to only 21% on placebo.

Important Considerations

Vyvanse is not a weight loss medication. It’s not approved or studied for that purpose. It’s specifically approved for reducing binge eating episodes.

That said, for patients with ADHD who also struggle with binge eating, treating the underlying ADHD often significantly improves eating patterns even without specific binge eating treatment.

If you have both ADHD and binge eating patterns, getting appropriate ADHD treatment (whether with medication or behavioral strategies) should be part of your comprehensive weight management plan, including your preparation for bariatric surgery.

The Hidden Diagnosis: ADHD in Women

I want to address something important: if you’re a woman reading this and thinking “could I have ADHD?”, the answer might be yes, even if you’ve never considered it before.

ADHD presents differently in women than in men, and diagnostic criteria were historically developed primarily through observation of hyperactive boys. As a result:

- In childhood, boys are diagnosed with ADHD at 3 times the rate of girls

- By adulthood, the ratio is nearly 1:1, suggesting massive underdiagnosis of girls

- The average age of diagnosis for women is in the late 30s to early 40s

- Women are more likely to have the inattentive type (difficulty focusing, forgetfulness, disorganization) rather than the hyperactive type

- Women’s symptoms are often misdiagnosed as depression, anxiety, or personality disorders

Signs of ADHD in adult women often include:

- Chronic disorganization despite repeated attempts to get organized

- Feeling overwhelmed by daily life

- Difficulty completing projects

- Constantly losing things

- Time blindness (chronic lateness, difficulty estimating how long things take)

- Emotional sensitivity and reactivity

- Racing thoughts

- Difficulty relaxing

- Impulsive decisions (spending, speaking, eating)

- Underachievement despite intelligence

- History of being called “lazy,” “spacey,” “scattered,” or “too emotional”

If this list resonates with you, and especially if you also struggle with your relationship with food, seeking an ADHD evaluation may be one of the most important things you do for your long-term success.

What This Means for Your Bariatric Journey

If you have ADHD (diagnosed or suspected) and are considering bariatric surgery, here’s what I want you to know based on my experience with thousands of patients:

Before Surgery

1. Get evaluated and treated for ADHD. If you suspect you have ADHD, pursue diagnosis. If you’re already diagnosed, optimize your treatment. This includes both medication (if appropriate) and behavioral strategies. Starting surgery without addressing ADHD is like running a marathon with a broken ankle. You can do it, but it’s unnecessarily hard.

2. Build your dopamine menu now. Start identifying non-food sources of stimulation and practice using them regularly. This needs to be in place before surgery, not after.

3. Develop structured eating patterns. Because ADHD affects interoception, you likely can’t rely on internal hunger/fullness cues. Work with a dietitian to establish regular meal timing, even when you don’t “feel” hungry.

4. Create external support systems. Use phone reminders for meals, appointments, vitamins. Partner with someone who can help with accountability. Consider working with an ADHD coach.

5. Honest assessment of emotional eating patterns. Identify when you use food for stress relief, boredom, procrastination, reward, or comfort. Develop alternative strategies for each of these needs.

After Surgery

1. Prioritize follow-up appointments. This is where ADHD patients most often struggle. Put every appointment in your calendar immediately. Set multiple reminders. Consider having someone else help you stay accountable.

2. Watch for transfer addiction. Be especially cautious with alcohol (I recommend complete avoidance for at least 12 months). Monitor for new compulsive behaviors around shopping, internet, exercise, or other activities.

3. Maintain structured eating. Post-surgery eating is highly structured by necessity in the early phases. As you progress, maintain regular meal timing even as your capacity increases. Don’t skip meals and then “catch up” later.

4. Take your vitamins consistently. Vitamin deficiencies are serious after bariatric surgery. For ADHD patients who struggle with routine tasks, this requires specific strategies: pill organizers, phone alarms, habit stacking with something you already do daily.

5. Continue ADHD treatment. Your ADHD doesn’t go away after surgery. Work with your prescribing physician to adjust medication doses as needed (absorption may change). Continue behavioral strategies.

6. Build movement into your life. Exercise is one of the most effective non-medication interventions for ADHD—it naturally increases dopamine and helps regulate mood and impulsivity. Make it part of your post-surgery lifestyle.

7. Get mental health support. Working with a therapist who understands both ADHD and eating issues can be invaluable. Many ADHD patients benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which can help with both ADHD symptoms and disordered eating patterns.

It’s Not About Willpower

If there’s one message I want you to take from this, it’s this: the connection between your ADHD brain and your struggles with food is real, neurological, and not your fault.

You are not weak. You are not lazy. You are not lacking in willpower.

You have a brain that works differently, and that difference affects eating in profound ways that most diet advice completely ignores.

Understanding this is not an excuse. It’s information. And with information, we can make better plans.

Bariatric surgery can be incredibly effective for patients with ADHD. I’ve seen it transform lives. But it works best when it’s part of a comprehensive approach that includes:

- Appropriate ADHD treatment

- Behavioral strategies for executive function

- Alternative dopamine sources

- Structured eating patterns

- Strong support systems

- Mental health care

- Awareness of transfer addiction risks

If you’re considering bariatric surgery and suspect that ADHD might be part of your picture, I encourage you to bring this up with your treatment team. The most successful outcomes come from treating the whole person, brain included.

Dopamine hunger describes eating driven by the brain’s need for stimulation rather than physical hunger. People with ADHD have lower baseline dopamine levels, causing their brains to constantly seek stimulation. Food—especially sugary, salty, or fatty food—provides a quick dopamine spike, making eating a form of self-medication for understimulated ADHD brains.

Research shows approximately 30% of adults with binge eating disorder have a history of ADHD. In bariatric surgery candidates specifically, studies find ADHD prevalence of 20-27%—significantly higher than the general population rate of approximately 5-10%.

Yes. Multiple studies show patients with ADHD achieve comparable weight loss to non-ADHD patients after bariatric surgery. A 2024 study found bariatric surgery was “highly effective and underutilized” in ADHD patients. However, ADHD patients benefit from extra support for follow-up attendance and monitoring for transfer addiction risks.

Signs of stimulation eating include: eating when bored (not hungry), needing to eat while doing something else, finishing meals but still feeling unsatisfied, seeking intensely flavored foods, eating past fullness without satisfaction, difficulty stopping once you start, and using food as your primary way to take a break or manage stress.

Transfer addiction occurs when people replace food as their primary coping mechanism with other behaviors or substances after surgery. Up to 30% of bariatric patients develop some form of transfer addiction, most commonly alcohol use. The risk is higher for those with ADHD, history of binge eating, or history of using food for emotional regulation.

A dopamine menu is a personalized list of activities organized by stimulation level—appetizers (quick boosts), main courses (sustained activities), desserts (easy but easily overdone), and specials (occasional high-investment activities). For people with ADHD, having pre-identified non-food dopamine sources helps prevent defaulting to eating for stimulation.

After bariatric surgery (especially gastric bypass and sleeve), alcohol is absorbed faster, blood alcohol levels rise higher, effects are more intense, and clearance takes longer. Many patients feel intoxicated from a single drink. This heightened response makes alcohol more reinforcing and potentially addictive. Studies show 20% of gastric bypass patients develop alcohol use disorder within 5 years.

Interoception is your brain’s ability to sense and interpret internal body signals like hunger, fullness, and thirst. People with ADHD often have impaired interoception, meaning they may not notice hunger until starving, can’t tell when they’re full, or confuse emotions (boredom, anxiety) with hunger. This makes regulating eating based on internal cues very difficult.

Yes. Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) is FDA-approved for ADHD (since 2007) and is the only FDA-approved medication specifically for moderate to severe binge eating disorder in adults (since 2015). It works by increasing dopamine and norepinephrine, reducing the drive to seek dopamine through food. Note: It’s not approved for weight loss.

ADHD diagnostic criteria were developed primarily from observing hyperactive boys. Women more often have the inattentive type (difficulty focusing, disorganization) rather than hyperactivity. Women’s symptoms are frequently misdiagnosed as anxiety, depression, or personality disorders. The average age of diagnosis for women is late 30s to early 40s—often after their children are diagnosed.

Ready to Take the Next Step?

If you’re struggling with weight and recognize yourself in this article, I’d welcome the opportunity to discuss your options. I take a comprehensive approach that considers your complete picture, including neurodivergence, emotional eating patterns, and individual brain chemistry. This is what sets my practice apart: I don’t just perform surgery. I help you understand why previous attempts haven’t worked and create a plan that actually addresses the root causes.

During your consultation, we’ll discuss:

- Your complete health and weight history

- Any ADHD symptoms or diagnosis

- Your relationship with food and eating patterns

- Appropriate surgical options for your situation

- What comprehensive preparation looks like for you

- Long-term support strategies

You don’t have to fight your brain. You just need to understand it and work with it.

Contact my office to schedule your consultation.

Dr. Gabriela Rodríguez Ruiz

Master Surgeon in Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery

Fellow of the American College of Surgeons

Board Certified by the Mexican Council of General Surgery

Member, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. ADHD diagnosis and treatment should be conducted by qualified healthcare professionals. Bariatric surgery decisions require individualized medical evaluation.